Songwriters are always looking for new ways to make their music more interesting and engaging.

One of the best ways to do that is by adding a key change.

Why?

Because changing keys in a song really makes an impact!

They’re a great way to boost your song’s energy.

They’re also a wake-up call to your listeners. They introduce an element of surprise and grab attention.

Even if your listeners don’t understand music theory, they usually notice that something different has happened in the song.

But since we’re songwriting pros (or at least serious about songwriting), let’s dive a little deeper.

In this post, you’ll learn the basics of key changes. We’ll review some music theory, and I’ll also give you examples to help you recognize and learn how to use key changes effectively.

Popular Key Signatures in Today’s Hits

There are several key signatures that are commonly used in modern pop music. The reason is simple — they’re usually in most singers’ ranges and also easy to play on both guitar and piano.

You can technically write a song in any key you like, but the original key you choose for your songs will often depend either on your own vocal range or the artist(s) that you’re writing for.

The emotion you’re going for will also play a role.

Major keys generally evoke brighter, more upbeat emotions while minor keys tend to feel darker and heavier.

In addition to emotion, you might want to consider instrumentation and arrangement. Do you have a lick, motif, or solo that you really want to include? Is there a key that it works best in (say from a fingering standpoint)?

The top key signatures in popular music today are C major and G major, along with their relative minor keys, A minor and E minor, with Eb/cm and F/dm coming in third and fourth.

Start wherever makes most sense for the song you’re writing.

Once you’ve decided on your original key, you can consider key changes.

Why Use Key Changes in Songwriting?

When key changes are done right, they can take your songs to the next level. When they’re used poorly, though, your songs can sound awkward or even downright cheesy.

And while you won’t use key changes in every song — or even in most of the songs you write — it’s good to know how to use them wisely.

When you do use key changes, they must make sense. They must fit your vision for the song.

Some good times to add key changes include:

- When you really want a middle or end section to “pop,” say in a high-energy dance tune, a sing-along anthem, or in a moving love story.

- When you want to really highlight contrasting emotions within the song.

- For added uniqueness, interest, and variety.

Even though you may not use them often, you’ll become a more valuable songwriting collaborator if you know how to write key changes well.

But first, let’s review some definitions.

What is a Key Change in Music?

Remember that every key has a tonal “home” — a root or an anchor tone. All the other notes in the scale relate to it and revolve around it.

Chords in the same key just sound right together. You can often predict where the music’s going next without even knowing the song.

Changing keys, or changing the tonal home within a piece of music, is known as modulation.

To listeners, it’s a noticeable difference in the way the song sounds. Changing keys shakes up the predictability of pop songs, introducing surprising, cool, and memorable elements.

There are several kinds of key changes and they’ll all have a slightly different effect on your songs’ energy.

Note, however, that changing keys within a song is not the same as transposing a song into another key. When you transpose, you raise or lower all the pitches in the song by the same distance — usually so you can fit the song into someone’s vocal range.

So how should you use modulation in your songs?

5 Tips for Using Key Changes (a.k.a., Modulation)

If your goal is to write for the masses (radio-friendly tunes for top artists), you should know that key changes aren’t often used in today’s most popular music.

You’ll find loads of examples from the ‘80s, ‘90s, and earlier, but fewer recent ones. Still, I’ll always tell you there are no hard and fast rules.

As long as you aren’t overusing modulation — otherwise, your songs might seem predictable or dated.

If you decide to move forward, keep these tips in mind:

1. Consider all your options first

If your goal is to increase a song’s energy, you can often achieve the same result by adding more instrumentation, increasing the volume in a certain section, and/or lifting the melody.

So make sure a key change is really necessary to achieve your objective.

2. Match your lyrics to the song’s energy

If a section of your song has become more intense, then your lyrics should reflect that intensity as well. Don’t confuse your listeners.

3. Keep song structure in mind

Never introduce a key change in a place where it doesn’t make sense — say, for example, by putting a drastic change in the middle of a verse or chorus. Key changes are most commonly used between verses and choruses, in bridges, or in final choruses.

Key changes within sections are usually subtle, or not even true key changes.

You can learn more about song structure in How to Structure a Song.

3. Moving down is harder to pull off

Modulating downward is doable, and there have been popular songs that use this technique, but avoid this approach if you’re a beginner.

4. Know at least the basic theory behind your key changes

You don’t have to be an expert in music theory and key changes don’t have to be complicated. But as a composer, do study what works and why.

Here’s a good place to start.

A Quick Review of Music Theory

Let’s do a quick review of some terms (and if you need more insight, check out A Beginner’s Guide to Chord Progressions).

Scale: A series of notes that follow a distinct pattern (like Do-Re-Mi, the major scale pattern).

Key: A family of notes, defined by the first note in the series, that follows a scale pattern.

Key formula: The chord progression patterns that fit into certain musical keys. You can see complete charts for major and minor chord progressions here.

Tonic: The root or first note of a scale, also the one that determines the key.

Relative key: Two keys that use the same notes, but in a different order.

Parallel key: Major and minor keys that have the same tonic (or root), but that use different pitches because they follow different scale formulas.

Next, let’s look at some common ways to change keys in songs, with examples.

4 Types of Key Changes

There are many ways to change keys, but these are a few of the most frequently used ones.

1. Relative key

Relative keys are major and minor scales that are related in that they have the same key signature. In other words, they use the same notes — but in a different order.

The more notes two keys have in common, the easier it is for you as a songwriter to find ways to make the key change as smooth as possible.

You can use relative keys to change from:

- A minor key to its relative major key (ramping up the emotion)

- A major key to its relative minor key (lowering the vibe)

The best way to explain this is by example. These are the pitches in the following keys:

C major = C, D, E, F, G, A, B

A minor = A, B, C, D, E, F, G

Note that these scales use all the same pitches, just in a different order.

G major = G, A, B, C, D, E, F#

E minor = E, F#, G, A, B, C, D

Notice that the minor key starts on the sixth of the major key.

You can find a complete list of relative major/minor pairs here.

Popular songs that use relative key modulation include:

- “Mirrors” by Justin Timberlake

- “One” by U2

2. Parallel key

When a major scale and a minor scale have the same tonic note, they’re called parallel keys.

For example:

The C major parallel minor is C minor.

C major = C, D, E, F, G, A, B

C minor = C, D, E♭, F, G, A♭, B♭

The A minor parallel major is A major.

A minor = A, B, C, D, E, F, G

A major = A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#

Notice that the scales don’t contain the same pitches because they follow different scale formulas.

A song that switches from a major to its minor parallel will seem to become darker or gloomier, while one that switches from a minor key to its major parallel will seem to become brighter, happier, and more energetic.

You can hear parallel key changes in these examples:

- “Funkytown” by Lipps, Inc. starts in C major and moves into C minor.

- “Norwegian Wood” by The Beatles switches between parallel D major and D minor.

Note that songwriters frequently “borrow” chords from parallel keys (without actually switching keys entirely) in order to make their chord progressions more interesting. This usually applies to songs written in a major key that borrow a IV minor chord or a VII♭ major from its parallel minor key.

3. Stepwise jumps

Stepwise jumps may be most familiar to you. They happen when the key is bumped up (or down, much less frequently) by either a half-tone or whole tone (one fret or two frets on guitar, respectively.)

Stepwise jumps have practically an opposite effect to relative key changes, because by simply moving up, you’ll encounter keys with very different notes and chords than where you started.

As a result, a half-tone jump will be noticeable to listeners, and modulating a full tone will have quite an impact.

Some examples:

- “Love on Top” by Beyoncé has 4 key changes, each moving up a half step. Listen to see if you can hear them all.

- “Wouldn’t it Be Nice” by The Beach Boys modulates downward from A Maj to F Maj.

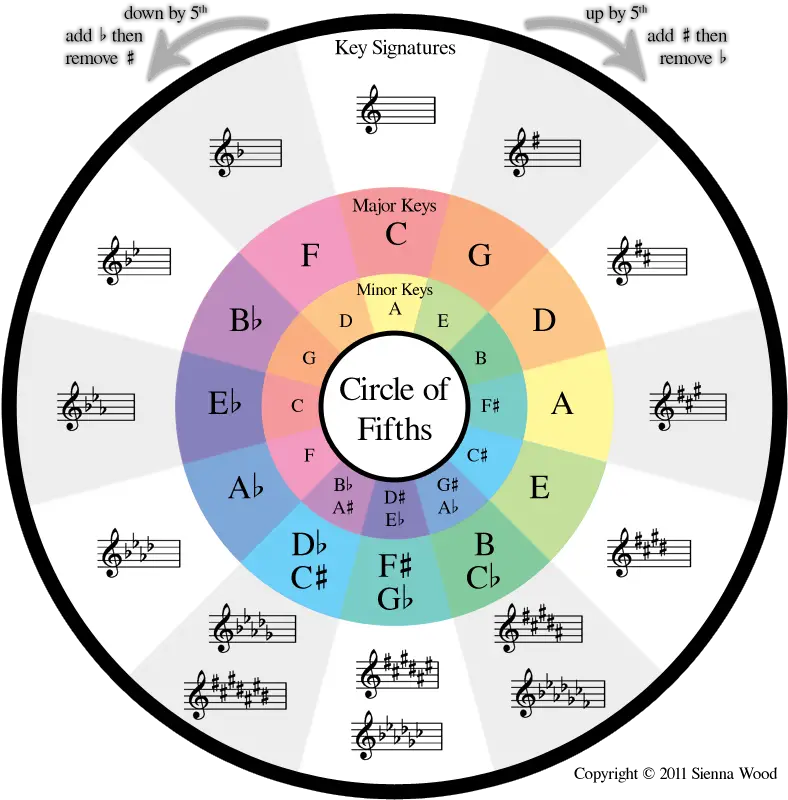

- Circle of Fifths

You can also choose to modulate to the next key moving along the Circle of Fifths.

When you move to the next position in the Circle of Fifths, there will be several chords in common.

For example, moving from D Maj to A Maj, you have:

D, Em, F#m, G, A, Bm, C#⁰

A, Bm, C#m, D, E, F#m, G#⁰

If you move from the key of A Maj to E Maj, you’ll have:

E, F#m, G#m, A, B, C#m, D#⁰

The best way to wrap your head around key changes is to listen to some examples and then try writing some for yourself.

Examples of Popular Songs that Use Key Changes

Here are some hits that you probably know well.

Can you hear the key changes when they happen? How noticeable are they? How do they make you feel?

- I Will Always Love You — Whitney Houston

- Creep — Radiohead

- Living on a Prayer — Bon Jovi

- Man in the Mirror — Michael Jackson

- Come on Eileen — Dexys Midnight Runners

- Money, Money, Money — ABBA

Write Unique Songs by Changing Keys

Next time you write a song that feels like it needs just a little extra push of intensity, think about adding a key change.

While you don’t want to overdo them, knowing how to artfully change keys in a song can make all the difference between a good-but-average song and an unforgettable one.

In the meantime, check out the examples in this post for inspiration and keep notes on any songs you find on your own.

And good luck!

Whenever you’re ready to write your next song, be sure to grab your copy of my “How to Write a Song” ebook.